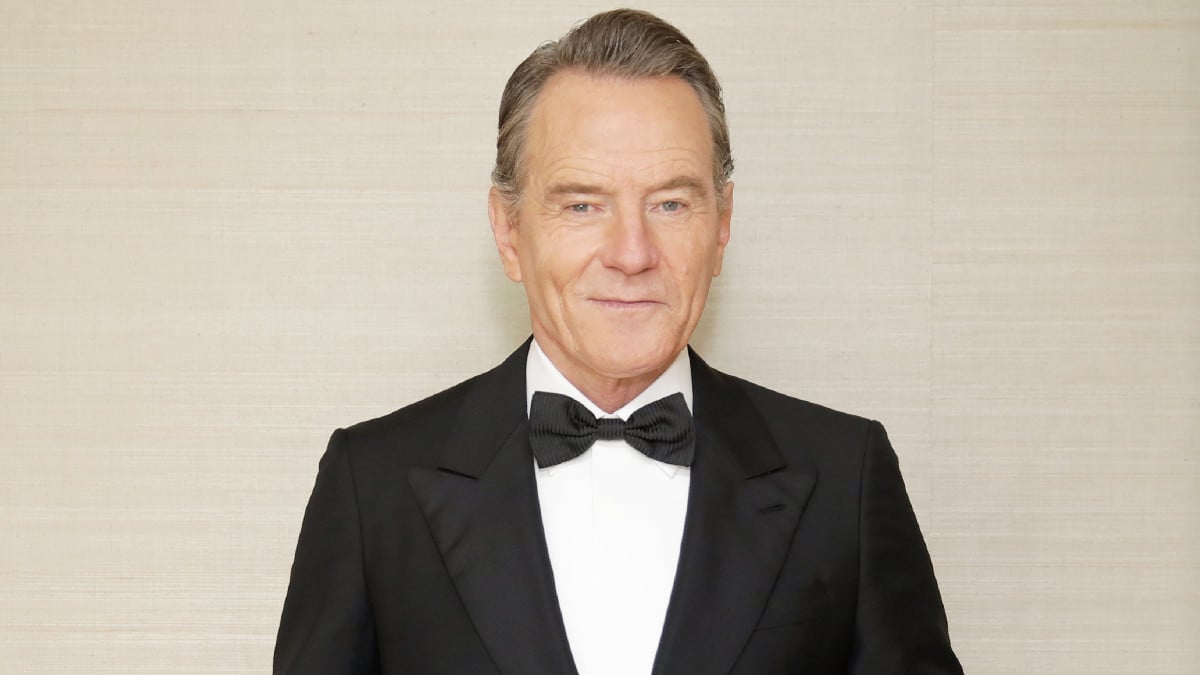

Bryan Cranston is currently appearing in a West Coast production of the play Power of Sail, about a Harvard professor who faces backlash after inviting a white nationalist and Holocaust denier to speak at his annual symposium, under the guise of tolerance and free speech. It’s a role that forced Cranston to examine his own white privilege, but so did the journey getting him there.

Before accepting that role, the 65-year-old actor had been planning on directing a production of the 1984 Larry Shue comedy The Foreigner, about an Englishman who prevents the Ku Klux Klan from converting the Georgia fishing lodge where he’s staying into a meeting place. Cranston had personally chosen the play, which he had long since been a fan of. However, he decided to reconsider the choice in the wake of nationwide protests following the police killing of George Floyd.

“It is a privileged viewpoint to be able to look at the Ku Klux Klan and laugh at them and belittle them for their broken and hateful ideology,” Cranston told the Los Angeles Times in an interview this week. “But the Ku Klux Klan and Charlottesville and white supremacists — that’s still happening, and it’s not funny. It’s not funny to any group that is marginalized by these groups’ hatred, and it really taught me something.”

“And I realized, ‘Oh my God, if there’s one, there’s two, and if there’s two, there are 20 blind spots that I have … what else am I blind to?” Cranston explained. “If we’re taking up space with a very palatable play from the 1980s where rich old white people can laugh at white supremacists and say, ‘Shame on you,’ and have a good night in the theater, things need to change, I need to change.”

Instead, Power of Sail, which first premiered at the Warehouse Theatre in Greenville in 2019, allowed not only for Cranston to confront his own privilege but added to a larger conversation — examining the generational divide that typically ensconces these arguments. It also asks whether there should be limits to free speech, as we’ve seen these types of disagreements play out on college campuses across the country in recent years.

“There need to be barriers, there need to be guard rails,” said Cranston, whose character dismisses the students as “babies” for voicing their concerns. “If someone wants to say the Holocaust was a hoax, which is against history … to give a person space to amplify that speech is not tolerance. It’s abusive.”

The past few years have forced a lot of white Americans to confront their own privilege, and Cranston feels that the play is resonating with viewers by opening up a dialogue to navigate these precarious, post-pandemic waters.

“A good play may not change your life, but it could change your day,” Cranston says. “To go deeper, a play can also stimulate the mind. It can make you question your thought process — your dogma. It could challenge you.”