An age-old argument is reignited each year as the breeze turns brisk and skeletons begin to populate local lawns. As Halloween inches closer, fans of the year’s spookiest season settle down in their themed sweaters, pumpkin spice lattes in hand, and prep to watch a myriad of carefully-selected films. Several staples of the season, like Hocus Pocus and Beetlejuice, are annual views, but one film remains a point of contention among viewers.

The debate around which season owns the rights to The Nightmare Before Christmas is as old as the film itself and crops up anew each time the holidays come around. Endless arguments support either side of the dispute, from the inclusion of Christmas in the title to the film’s setting in Halloween Town. The subject recently tore the We Got This Covered newsroom asunder, so we gathered here to collect our thoughts and share them with the world. It’s ultimately up to you, dear reader, to decide which side makes the stronger argument. We highly advise that you enjoy the film during both holiday seasons, but if you had to choose one: is The Nightmare Before Christmas a Halloween film or a Christmas classic?

It’s a Halloween movie

Like my opponent, I’m of the opinion that Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas is simultaneously a Halloween movie and a Christmas movie. However, I’m in the camp that says it verges far more towards the status of a Halloween movie, a belief that’s chiefly rooted in the fact that the film celebrates the triumph of not only Halloween, but of an entire ethos that surrounds the holiday.

First, background info; Christmas is a high-profile extension of spiritual Christianity, whilst Halloween is historically rooted in the more earthly paganism. Keeping this dichotomy in mind alongside both of their relationships to scientific and mythopoeic thought, we can ultimately declare that Halloween essentially used Christmas as a springboard for its own ideological triumph.

We’re immediately introduced to Jack Skellington, our champion of Halloween. He’s fed up with the monotony of the holiday and is desperate for change.

Jack soon identifies Christmas as the potential saving grace for his boredom, and this is where the dichotomy between Christianity (Christmas) and paganism (Halloween) becomes important.

Paganism, at its most basic, places value in the earthly (i.e. pleasure for the sake of pleasure, indulging for the sake of an observable, often biological, want or need, with almost all of the emphasis on the observable world).

Christianity, meanwhile, places value on the spiritual (i.e. behaving in a way that subscribes to an unobservable approval (in Christianity’s case, heaven), with hopes of having done what’s expected of a “good” person so that they may enter this unobservable heaven as a sort of reward, generally not taking into account whether their actions feel or are otherwise observably beneficial to them in the moment.

These two ideologies can even be traced up to some of the nuances we come across in modern-day celebrations of either holiday, chiefly in the relatively-excessive consumption of candy (pleasure for the sake of pleasure) on Halloween, and Christmas’ age-old ethos of believing in an unseen figure (Santa Claus) in hopes of appeasing them (“Have you been good for Santa this year?”) for the sake of a reward (Christmas presents).

In short, the two holidays could not be more fundamentally opposed, and this is an oversight that Jack — who himself embodies Halloween — makes when he seeks to essentially cut and paste what he knows over to a Christmas celebration, which culminates in the macabre fiasco he creates on Christmas Day.

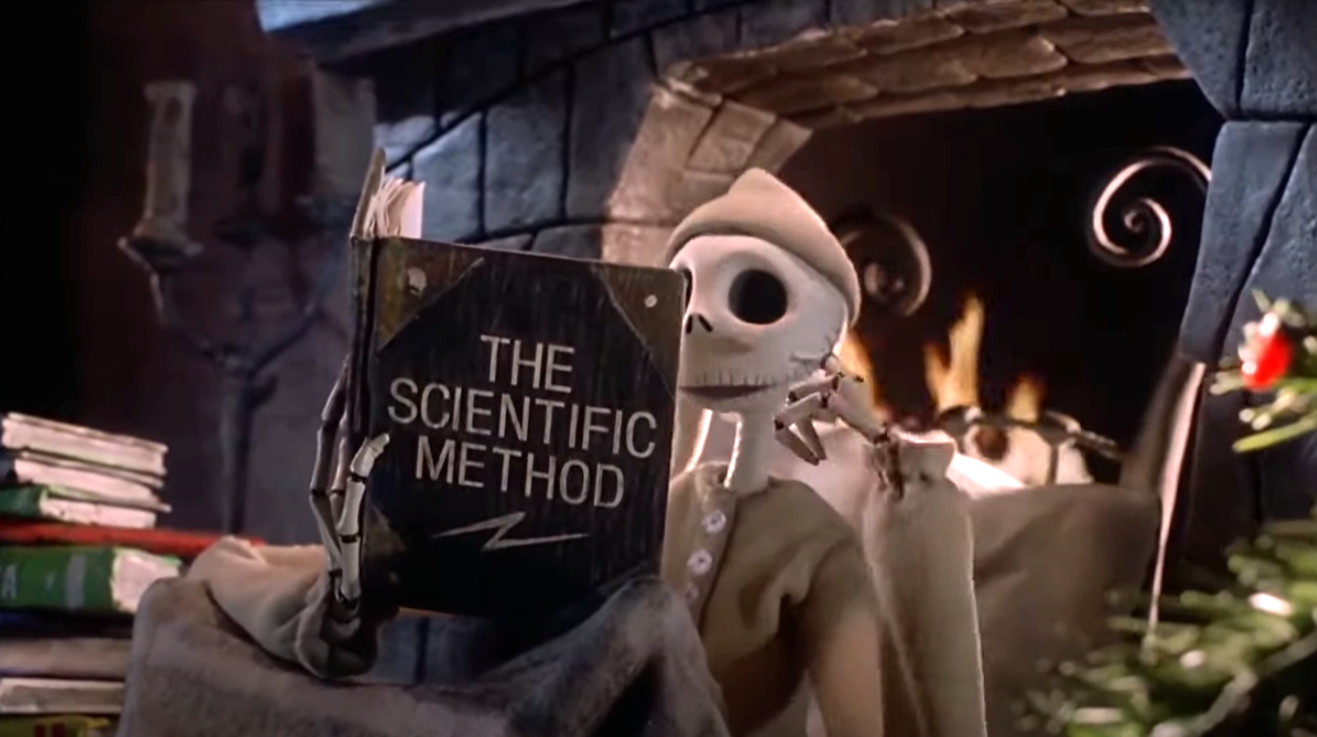

Now, Jack’s consultation of the Scientific Method (as he is shown doing above) is an important development here and is perhaps best explained when understood in opposition to mythopoeic thought.

Simply put, mythopoeic thought understands the world through a lens of “x does this because x wants to do this.” This contrasts with scientific thought, which understands the world by observing the many different parts of it and the reactions between them, with the goal of declaring one’s own understanding upon it. In other words, scientific thought seeks to place oneself in a higher position than its subject, giving ultimate superiority to what one already knows or believes, or at the very least, declaring a truth upon the subject that is simply most convenient for one’s current ideological and intellectual standpoint. For example, we understand a tree as a tree, but we only understand a tree as a tree because we designated it as such using language, so a tree being a tree is not an absolute truth, but simply an understanding that’s convenient for us.

This is something that Jack does to Christmas by taking his understanding of the world (which, at this point, consists almost entirely of Halloween-centric ideas and motifs) and forcing them into the holiday, which, again, causes the disaster of a Christmas Day that occurs in the second half of the film, largely due to the incompatibility between the two holidays.

But it’s when Jack realizes this mistake that the ultimate triumph of Halloween begins to take shape. While still largely belonging to the ideas represented by Halloween, Jack’s exposure to and participation in the fundamentally spiritual Christmas, no matter how perverted his approach was, has granted him the gift of expanding his (Halloween’s) own ideological horizons.

It’s also around this time that the film acknowledges that Halloween (earthly values) is not inherently superior via its portrayal of antagonist Oogie Boogie, whose gambling aesthetic indicates that this is someone who indulges in pleasure for the sake of pleasure (i.e. gambling for the serotonin boost) in a way that’s ultimately harmful.

What’s more, Jack’s musical number around this time firmly indicates that the experience has granted him a renewed sense of goodwill for Halloween, i.e. earthly values, i.e. pleasure for the sake of pleasure/doing something for the sake of solving a palpable problem or desire. And just like that, Jack is back to embracing not only the earthly values that Halloween embodies, but also understanding that it comes with a dash of the mythopoeic, which suggests a dismissal of the scientific angle he once embraced (i.e. “I’m going to save Christmas because I want to save Christmas”).

And how does Jack fulfill this desire to save Christmas? By enabling the person who can save Christmas — Santa Claus. We can then read this decision as Jack’s full rejection of scientific thought (and newfound embracing of mythopoeic thought), and his subsequent return to his earthly roots; he (Halloween) is no longer declaring his own pre-existing understandings upon Christmas, but is instead choosing to live alongside it and understand it as its own entity that cannot be defined by his pre-existing knowledge (Santa Claus himself, then, represents this separateness of Christmas that Jack is now respecting).

Knowing all of this, his desire to save Christmas (itself an earthly value) will logically lead him to the decision of simply doing what needs to be done; in this case, freeing Santa Claus from Oogie Boogie so that he can go and save Christmas.

So, it’s Jack’s reclamation of these historic values of Halloween (earthly values and his newfound mythopoeic angle that further bolsters these values) that allow the film’s protagonists to ultimately triumph in their endeavors. The cherry on top of it all is his kiss with Sally at the end of the film; Sally warned Jack of the dangers of his original quest throughout the film, and she is also someone who’s already familiar with the dangers of scientific thought (as represented by her scientist father/captor Doctor Finkelstein). Their romance, then, seals the deal on Jack’s newfound knowledge and restored values that he acquired over the course of the film.

Thus, while Christmas was an important part of the story, it ultimately becomes a tool that Jack uses to instill within him a new appreciation for Halloween and its subsequent thematic values, both of which proceed to flourish upon his decision to save Christmas. And thus, the film is a triumph for Halloween, thus making The Nightmare Before Christmas a Halloween movie. Cue the opening musical number. — Charlotte Simmons

It’s a Christmas movie

Nightmare Before Christmas is undeniably a celebration of both Halloween and Christmas, but I’m here to convince you that the film leans far harder in a Yuletide direction.

My argument boils down to one singular point, with plenty of minor takeaways and notes to add flavor. There are six essential elements to crafting a story, and every tale requires these elements to be met before its story can feel complete. Some, like the setting, characters, and plot, are obvious, but several of the others can be more subtle. Every story requires a conflict, to push the narrative along and give viewers a reason to stick around, as well as a theme and narrative arc. These elements are the bones of a story — the structure that makes it into something interesting, thrilling, and worth absorbing.

In Nightmare Before Christmas, each of these elements is built around the Christmas holiday. The film’s narrative arc begins with its setup in Halloween Town, where Jack is shown to be dissatisfied and depressed with the current state of his life. The tension gradually builds as the disillusioned lead seeks a path away from the endless humdrum of his spooky-themed life, and he finds it in Christmastown. I would argue, were this not a Christmas movie, that Jack’s journey could have taken him through any of the other holiday doors. It is his decision to venture through the tree-shaped doorway that makes Nightmare Before Christmas what it is, not his origin in Halloween Town.

Most importantly, the climax of Jack’s story is inarguably tied around Christmas. His obsession with the holiday, which we see spark the first sign of joy in the formerly passionless character, is what drives Jack through the remainder of the film’s storyline. And considering he stumbles across Christmas Town less than 15 minutes into the hour and some change film, it’s clearly the dominating factor that drives the story onward.

Yes, Jack later returns to Halloween Town, and many of his interactions are clearly built around the inherent “Halloweenness” of his fellow characters, but everything is built around the same goal: to bring Christmas to Halloween Town. Halloween is clearly a vital factor in the story, but it is not the commanding element.

Nearly everything considered good and wondrous in the film is based around Christmas, not Halloween. It’s enhanced by the humorous failures of Halloween Town’s residents to capture the magic of the sister holiday, and this — more than anything — feels like the theme of the movie. We can all see ourselves reflected in the odd, out-of-place characters scattered around Halloween Town, but that’s not the purpose of the film. The purpose is to alight in us, just as it alit in Jack, a true sense of wonder and joy at the thought of Christmas.

Throughout the film, Christmas remains a lofty, tantalizing goal, one which is only intensified by the purposeful dichotomy between its themes and those in Halloween Town. This clash only serves to highlight Christmas even more and to exemplify that it is for absolutely everyone, including those that wouldn’t normally consider themselves part of the Christmas fold.

This is demonstrated in every element of Nightmare Before Christmas, from its dialogue and music to its color scheme. The colors and characters in Halloween Town are muted and washed out, while the entirety of Christmas Town is vibrant, bright, and full of life. These elements, purposefully laid out as thrilling and alluring, are intended to make the audience lust after Christmas Town in much the same manner as Jack.

It feels necessary to reiterate that relegating this film to a single holiday is nothing short of criminal. Why, when a film so wonderfully suits two separate holidays, would we restrict it to only one? But I argue that the next time you enjoy the delightful Tim Burton flick, you’ll find yourself pining for Christmas, even as you watch the denizens of Halloween Town dominate the film’s screentime. — Nahila Bonfiglio