It’s been a strange few years for Disney. It’s been (rightly) praised for taking a strong stance against Ron DeSantis’ backwards, bigoted laws, but its diversity push is producing some mixed results, alongside the inevitable backlash from people who think a half-fish, half-human is only plausible if they have skin that burns at the first sight of sun. A mixed bag for the House of Mouse, to say the least.

Creatively speaking, though, it’s been a dull period, and it seems like Disney is producing nothing but live-action remakes, reboots, and sequels. With Peter Pan & Wendy set to be released next week, as well as the news that Toy Story is coming back for a fifth film and Moana is getting a reboot, it seems prudent to ask: has Disney completely lost any sense of creativity? And is this just a Disney problem? Or, despite what plenty of people think, is it really a problem at all?

The most obvious culprit for this reliance on tried-and-tested tales is the fact that Disney is primarily a profit-driven endeavor, and — like most huge companies — the notion of shareholder primacy has a huge hold on all its business decisions. A rehashing of old stories guarantees a built-in audience of people who know and love the characters, which means a greater chance of making money. Add in the fact that Disney has a larger proportion of shares held by institutional investors than any other media conglomerate, and you get a world in which creativity is sacrificed for safety and profits. But hey, at least someone’s happy, right?

This doesn’t apply so much to independent films and smaller studios, who often produce daring and intriguing content, even though they generally have much slimmer margins to work with. If you’re willing to look for it, there’s plenty of great cinema out there still. But because some people think Mr. Burns isn’t a parody but in fact a shining example of how to live, big companies that make blockbusters — like Disney — will almost always default to a remake, sequel, or reboot.

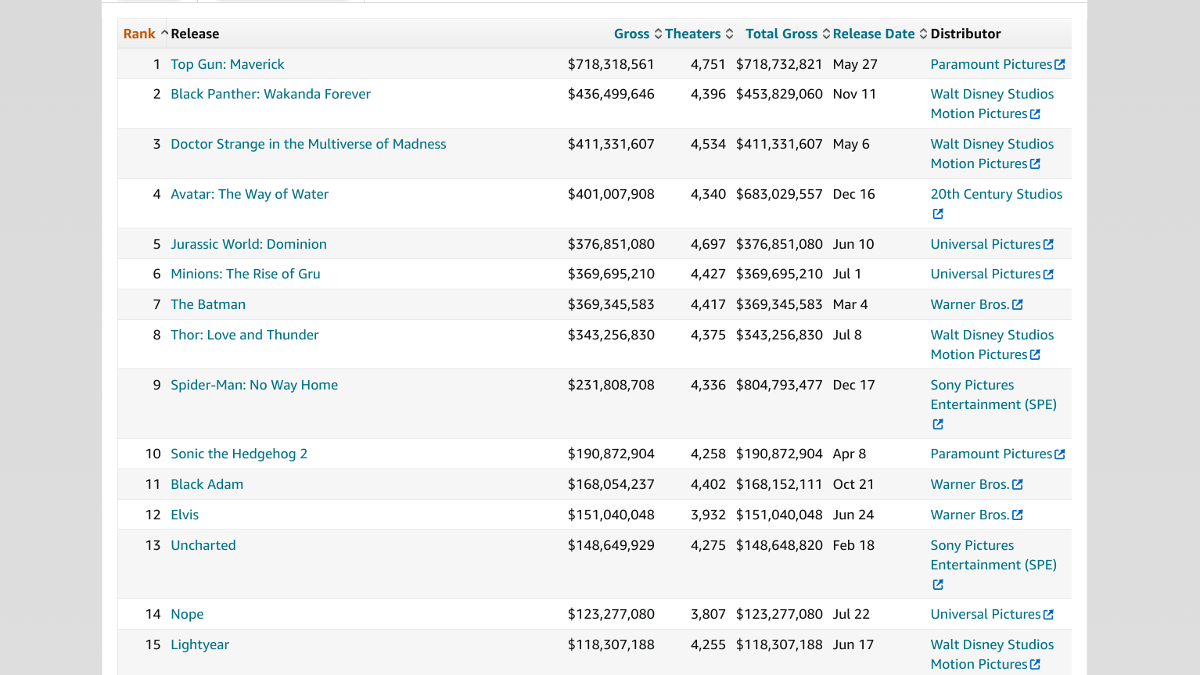

Think about some of the most popular films of recent years: Avatar: The Way of the Water, Top Gun: Maverick, A Star is Born (a remake of a remake). Some days it can feel like the world ended and was replaced with the purgatory of a seemingly endless slew of Fast and Furious films. A look at the top-ten grossing movies of 2021 and last year shows the problem is deeply rooted: of the twenty flicks, nineteen were sequels, remakes, or reboots.

It’s ironic that the only holdout was the Disney-produced Free Guy, because the company is one of the worst offenders when it comes to reusing existing content. Take, for example, Cruella (2021), a prequel to 101 Dalmations, which in turn was a live-action remake of the animated film of the same name. This endless exploration of already mined universes could be an interesting thing, but remakes (especially live-action ones) are often plagued by bad writing, as well as simply missing all the charm of the originals.

The originality problem is also driven by issues around intellectual property. When the NPR podcast Planet Money lightheartedly tried to buy the rights to literally any Marvel and DC characters they were denied. One of the main reasons for this was the ultra success of Guardians of the Galaxy, which turned seemingly unloved and forgotten characters like Groot into global superstars, and therefore profit machines. Now, studios and companies are desperate to hold on to any and all intellectual property, just in case it comes up trumps at some later date. This is also why newer largescale content creators, like Apple TV and Netflix, don’t really do remakes to the extent that legacy studios do: they don’t have the sheer depth of content that allows them to reboot and remake favorites that they know fans will turn to like comfort blankets – but they will soon.

Of course, Disney has always been stingy with its characters. They’ve developed a reputation for being incredibly litigious, using their wealth and power to make sure that courts rule in their favor in cases when it comes to protecting their intellectual property. While the rabid nature of their legal battles is generally seen as a bad thing for creative endeavors, Disney’s army of lawyers has, at least, given us some hilarious outcomes when it comes to their fight against Ron DeSantis – so it’s not all negative.

The obvious solution to this is to try and rally audiences to vote with their wallets, but that ignores the reality of life for many in the western world (especially since the 2008 financial crash). Broadly speaking, the cost of living has gone up without a comparable rise in wages, especially if you are lower or middle class. This means people are less likely to spend their hard-earned cash on something they might not like, and reboots have the benefit of offering both a familiar story and an element of nostalgia. Combined with an endless news cycle that regurgitates partisan talking points, social media that turns people into outrage addicts, and the never-ending belief that things were “better in the old days,” and you have a perfect storm for people wanting to escape into something comfortable – like a third Frozen film.

There is one supposed positive of the endless reboot and remake culture that seems to have its claws in Disney, and that’s the notion that the near-guaranteed trickle of money from these much-beloved characters and creations means studios can finance some riskier, more unique projects. Original movies like Inside Out prove that this sometimes does happen, but given the upcoming slate of Disney releases, it seems like a novel idea is becoming increasingly rare. This problem is especially acute when you look back to the nineties and early 2000s, when Disney (and Pixar in particular) released new hit after new hit. Whatever creative tap was flowing freely back then seems to have been twisted shut.

With that all said, remakes and reboots of films are not a new phenomenon – they’re just shoved in our faces a lot more now. Some of the greatest films of all time are remakes. The Magnificent Seven is an American remake of Seven Samurai, and John Carpenter’s iconic horror The Thing is a remake of a 1951 black-and-white film titled The Thing from Another World. The Departed, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Ocean’s Eleven, The Fly, and even the iconic Marilyn Monroe flick Some Like it Hot are all remakes too. And, of course, many supposed new films get their source material from short stories, books, and magazine articles. Heck, even our complaints about remakes aren’t new, as shown by this decade-old Reddit thread.

Plus, viewers have to take into account that when we think about old, iconic films, we’re thinking of those that have stood the test of time. In fifty years, the animated version of The Lion King is more likely to still be essential viewing compared to the live-action remake, which might even be forgotten. It makes sense we all think creators nowadays are devoid of ideas; we’re seeing the past through rose-tinted glasses, and signalling with our spending that we want to be swaddled in nostalgia. And it’s not just films that have this problem: think of the endless book series of all genres, especially those that are commercially popular (crime, romance, fantasy).

The thing is, though, Disney still has the pull to get great minds on their projects. It has all the tools available to head back to its creative heyday because, in terms of profits and influence, the company is at a definite peak – so much so it’s willing to take on the state of Florida. But putting growth above all else has come at a cost, and at some point a decision will have to be made: keep buying up franchises like Star Wars to suck them dry, or see if some creatives can recapture the magic that Disney held onto for so long.

Then again, it’s not like the Disneys of the world are literally making us watch their content; marketing is powerful, but not quite at mind control levels yet. If you’re bored of the idea of yet another Cinderella film, then the best thing you can do is support indie films and studios, or, on the rare occasion a new, big budget film comes out that isn’t a reboot, make sure to go to the cinema to watch it. Otherwise, we’re going to be rebooting this argument forever and ever.