Children of the ‘90s have a lot of strengths. We can spot, with a nearly inhuman level of accuracy, why kids love the taste of Cinnamon Toast Crunch, and their make-lemonade attitude about accidentally overloading a Cap’n Crunch factory’s berry production line, despite being an objectively enormous “Oops,” has led to decades of unprecedented sales growth for the Quaker Oats Company. In hindsight, most of what we’re good at has to do with cereal. You take the advantages you can get in this world.

We also have our weaknesses. One such weakness is, undeniably, an affinity for Hocus Pocus, an absolutely bonkers entry in the Walt Disney catalog of motion pictures. Boasting heaping scoops of weird horniness, immolation, outright in-universe evidence of the existence of a Christian afterlife, and Sarah Jessica Parker, there is no single frame of this bizarre movie that nostalgia-drunk fans don’t love.

But is it the most bananas big-budget ‘90s movie ever aimed straight at kids? Not by a long shot. Was Hocus Pocus directed by a man who had previously worked on the TV show Cop Rock? Was it written by the voice performers behind Slappy the Squirrel and The Brave Little Toaster, with an uncredited rewrite by JJ Abrams? Did it end with a father’s implied approval of his 13-year-old daughter living with her intangible, consequence-proof boyfriend?

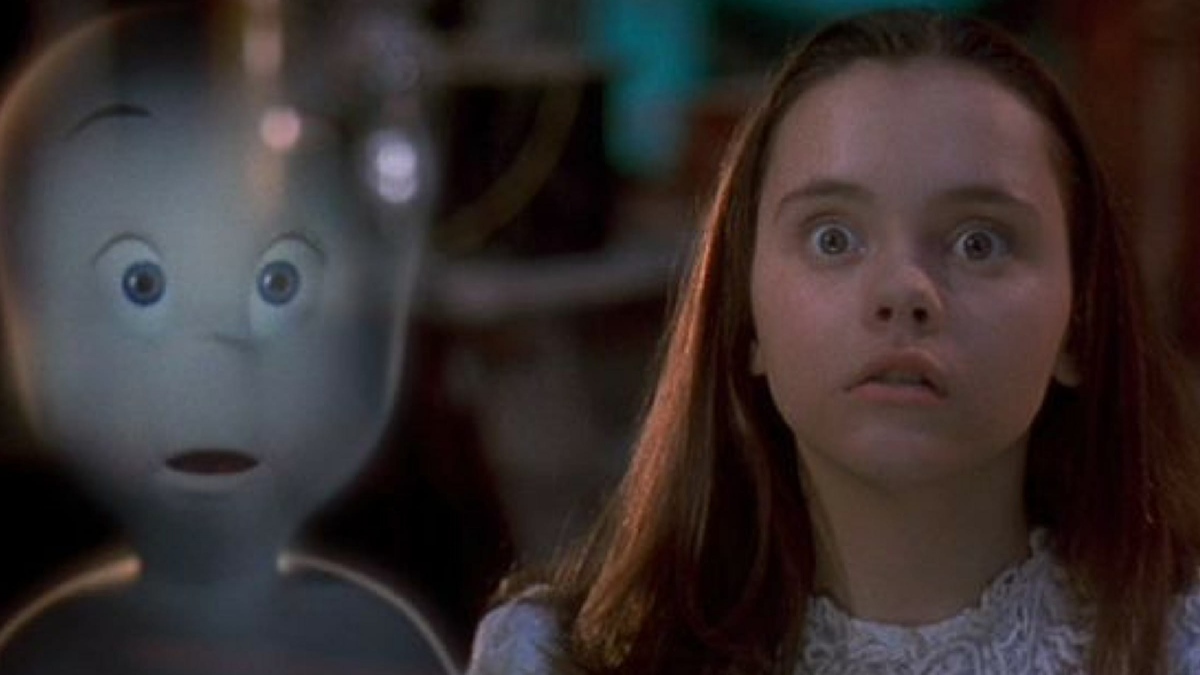

No, friends. Those honors can only be claimed by one children’s movie: Casper, the 1995 adaptation of the beloved Harvey Comics character that dared to ask the hard questions, like “do you think kids will get a kick out of this Father Guido Sarducci reference?” and “who cares if we’re making a whole generation afraid to go sledding?”

Casper‘s plot weirdness can’t be beat

Rewatching it today, it’s difficult to overstate just how much of Casper feels like a half-remembered nightmare – not in a spooky-scary-skeletons kind of way, more in the vein of realizing that “oh yeah, Mel Gibson makes a cameo.” With the understanding that any forthright synopsis will sound like the string-of-consciousness ravings of a dehydrated Burning Man first-timer, the plot goes something like this:

An obsessed widower is hired by a mean lady to remove the ghosts from her inherited mansion after SNL alumni Dan Aykroyd and Don Novello can’t do it, and get horribly disfigured, respectively. The obsessed widower moves in and connects with a trio of dead people, who warm up to his presence and eventually try to murder him so that he’ll join their gang forever. They fail, but he gets drunk and falls into a pit and dies instantly without their help, all by himself.

Meanwhile, the obsessed widower’s tweenage daughter gets hit on by a boy who died of pneumonia, driving his own father to madness and inspiring him to build a steampunk machine that cures death. On finding said machine, the dead boy gets really stoked on the idea of having a body again so that he can kiss the tweenage girl, but then the ghost of the obsessed widower shows up and uses the last of the death-cure juice to return to life, presumably leaving his fully-clothed corpse in the construction pit where he fell earlier, which you have to assume is going to lead to some questions from the police. The dead boy is sad, having missed his window to try kissing, but then the obsessed widower’s dead wife shows up, backlit with the intensity of a thousand Touched By an Angel denouements, and grants the dead boy’s wish to be alive and the future star of Final Destination for a few hours so he can go and kiss her daughter. Also, the mean lady from earlier dies, becomes a ghost, and then goes out basically the same way as Jafar at the end of Aladdin after murdering a member of Monty Python.

This is all a simplification, of course. Other stuff happens. The main character briefly turns into eggs, and the sad widower briefly becomes Rodney Dangerfield. There’s a very real, traceable plot under all of this, but it’s secondary to Cryptkeeper cameos and visual walk-throughs of the undead digestive system and a general sense that, somewhere along the line, maybe somebody in charge should have said “no,” even just once, even if it had just been regarding the scene with the monologue about child death. It’s been close to 30 years since Casper hit theaters, dividing critics into two camps: People who hated it, and people who thought that this CGI malarkey was pretty neat. Maybe it’ll never get the same cult love as Hocus Pocus. Maybe it’s not as deserving of that love as Hocus Pocus. But it’s definitely weirder than Hocus Pocus, a movie where a group of kids murder women so that a cat can go to heaven. If that’s not worth celebrating, nothing is.